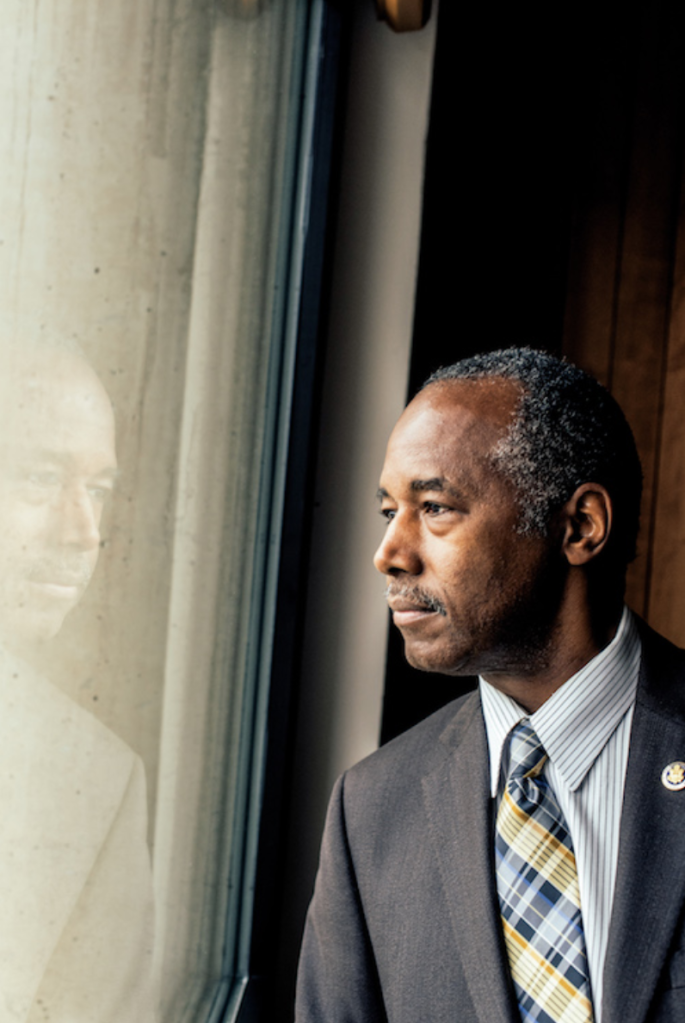

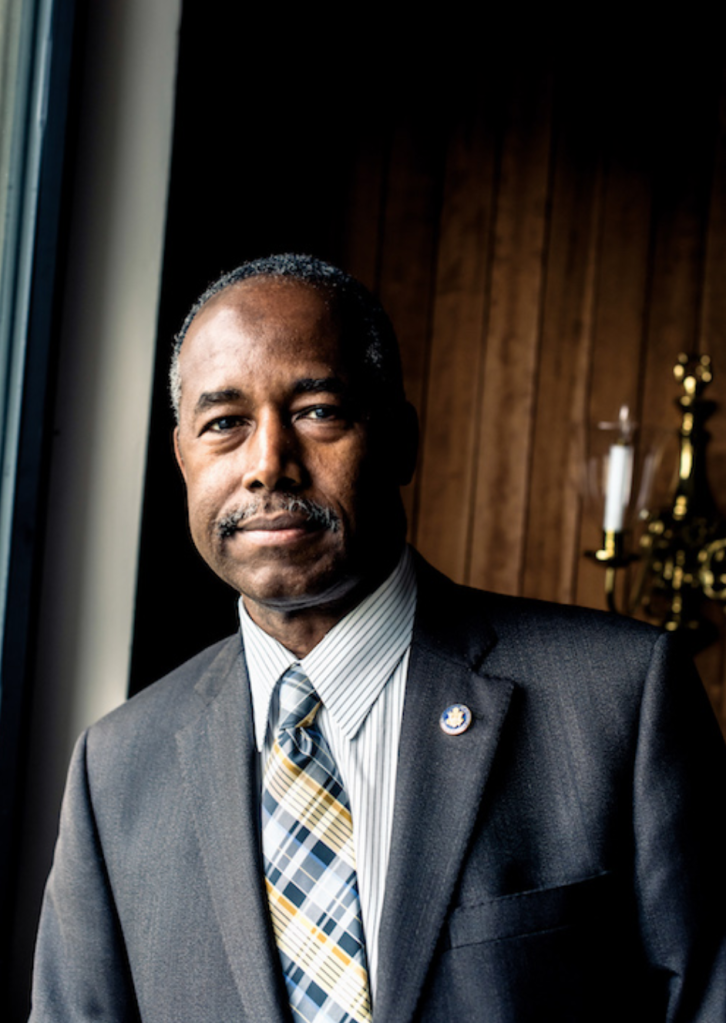

Photos by Stephen Voss

It’s a cold and rainy morning in Washington, D.C. and the streets outside the Robert C. Weaver Building, home to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, are puddled up with rainwater. A group of people waiting for the next bus huddle together, their umbrellas interlocking like a Roman Tortoise formation, just a few feet away from the sheltered bus stop, which is being regularly splashed by passing taxis.

The mildly irritating rain shower suits the so-called “soft” brutalist architecture of the HUD headquarters; its load-bearing, precast concrete façade seemingly absorbs the bad weather so much so that I convince myself more than one spot inside is probably leaking. Surely somewhere there must be a handy bucket deployed to catch drips from the ceiling, the water level constantly monitored by the maintenance crews.

Indeed, inside the lobby there are several maintenance workers gathered in front of the elevators. Although their clothes are lightly soiled with sheetrock, grout and even a splash of white paint, their work is — through no fault of their own — slow moving. Ever since the Weaver Building made the National Register of Historic Places, there are limits to the type of work they can do. Large-scale renovations of any kind are almost certainly out of the picture. Even the tiles in the bathrooms must be carefully removed, not to crack a single one, as every object is deemed worthy of preservation.

The Weaver Building serves as HUD’s spiritual home because most HUD employees are in field offices across the nation, not regular attendants in the building. Secondly, the physical conditions of the interior are routinely panned by workers on the department’s online message board. There is no love lost by workers when it comes to the design of the Weaver Building, so any of their affection toward HUD comes from the mission itself, not the location of their desks.

Back in 2014, one worker published a post titled “Petition to move out of HUD HQ Building or do a Complete Remodel”: “The morale in HUD is down because of a number of factors, but once you walk through the halls of the HUD building you’ll know one reason why right away — the depressing building. People need a good work environment, better atmosphere, and a place where they can come to everyday without becoming depressed or sick.”

This prompted a reply from HUD’s general counsel at the time, Helen Kanovsky.

“I want to be unequivocally clear on this one: HUD strongly supports a complete remodel of the Weaver Building that would ensure our headquarters employees are working in a safe, clean, modern office building…

“In recent years, we’ve worked with GSA [General Services Administration] and Congress to secure funding for a move or remodeling of this scale, and unfortunately haven’t received it. Absent that funding, there’s simply nothing we can do by ourselves to make this happen. Apologies for the bad news, but just know that we are working tirelessly to secure some of that money for future years, and hope to one day have better news on this front.”

Kanovsky never fulfilled that hope and would later jump ship for the Mortgage Bankers Association in 2016. Indeed, the role the Weaver Building physically exemplifies is not unlike the general opinion of HUD itself: clunky, underfunded and unloved.

This architectural rock and a hard place makes for a challenging work environment, and current Secretary Ben Carson was braced for a fight for loyalty from the moment he started.

But before getting into his first day experience, one question needed an answer, more than any other. Why would the famed neurosurgeon, prolific author and unsuccessful 2016 presidential candidate hold even a remote interest in entering the public position of a cabinet member to the very guy he lost the Republican nomination to?

INTRODUCING OUR 17TH HUD SECRETARY

To answer that last question, and more, Carson arrives early to our interview in his office. It’s as dated as the rest of the building, with 60s-era wood paneling covering the walls. There are comfortable furnishings, however, and the secretary has made himself at home, adding four pictures of his family to the walls.

A copy of the Israel Test is stacked on the bookshelf behind his desk, cover facing out. The tome by economist George Glider makes the case that Israel is the most tested capital market and tech heaven in the world. With a collective mentality among its citizens to lead the hostile nations around it into freedom and success, the Israel Test judges global societies by their attitudes toward the controversial Jewish state. To own it is a must for anyone interested in gaining financial acumen, but to openly display it? Purely bold.

Carson’s people, who agreed to the exclusive sit down with HousingWire, are a testament to the environment of cooperation Carson clearly wants. His people include new hires as well as the old guard, working together to try to spread an honest assessment in the housing finance industry’s most respected publication. I would have settled for a phone call, but to meet in person, at his office? “We like to under-promise and over-deliver,” one of his staffers explained.

The secretary invites me to sit in one of the chairs arranged around a coffee table in his office; not at his desk, not in the nearby conference area. Just two guys settling in for a chat.

We briefly speak for a moment about his books and then jump right in, as I don’t want to waste the extra 10 minutes Carson’s earliness allows for, and ask why he took the job.

Like any good public speaker, Carson opens the answer to his first question with a joke. “I was determined I was not going to take a job in this administration,” he said with a bit of a chuckle.

However, his family felt the opportunity was too important. The issues HUD deals with strike too close to Carson’s need to cure people of whatever sicknesses they face. As a doctor, his natural instinct is to heal and do no harm.

“We have to change the way we treat some of the disadvantaged in our society,” Carson said.

And he was braced for a struggle; Carson felt going into the role on day one, there would be some resistance from staffers. Certainly people enter into civil service with a mindset to serve their fellow Americans. Would the unexpected decision to place a world-renowned neurosurgeon in the role of the most powerful person in housing strike a wrong nerve with the more senior people at HUD?

Carson thought perhaps so, but his first day on the job proved full of surprises, as has every day since.

“I was told that it was a culture of inefficacy and laziness and to expect a lot of people to try to sabotage what I was doing; and that is the history of the place and that’s just the way it’s going to be. And, I didn’t find it to be that way at all.”

What he did find was an eager staff, regardless of tenure, be it four months at HUD or 40 years. The core belief in the mission was a strong part of the culture there — difficult office conditions or not.

“They all had this calling to help others, so as long as you include them, not talk down to them, they can prove to be extremely valuable allies to have. The fact that career people could stand up, not do what others told them to do, was quite pleasantly surprising.”

But as recent events in Washington show, the impressions and opinions of the movers and shakers in the nation’s capital don’t always align with the customs and behaviors of the nation at-large.

And, if his experience inside the Weaver Building was pleasantly surprising, it was his experience in the field that really blew him away. His early travels as HUD secretary included time spent in field offices, but his time on the ground during the unprecedented hurricane season this year impacted Carson the most.

STORM SURGE

Hurricane Harvey made landfall near the Gulf Coast town of Rockport, Texas, on Aug. 25. It was the first hurricane to cross an American shoreline in 12 years and it made up for that absence with a vengeance.

Federal Emergency Management Agency Administrator Brock Long would later refer to Harvey as a wake-up call and say it could end up as the worst disaster in Texas history. Economic losses are staggering, with a large portion of the losses sustained by uninsured homeowners.

Black Knight predicted the mortgage industry could see up to 300,000 new delinquencies as a result of the storm, with 160,000 borrowers becoming seriously past due. Recovery may take years. The federal government quickly pushed through legislative aid packages with unprecedented bipartisan support, uncharacteristic for today’s modern political climate.

Carson visited Houston on Aug. 29 and experienced firsthand how HUD employees respond in times of a real crisis. The amount of manpower humbled Carson, as did the attitudes he encountered. He was there to make sure he could help ensure things went as smoothly as possible, but without getting in anybody’s way.

“There are more HUD employees outside this building than inside this building. And I want to hear from them. What are your problems between your field office and the central office?”

“In terms of Texas, I’ve been there two times and will be going many more times, they’ve really jumped on the situation,” he said, adding that in the wake of Hurricane Harvey, HUD quickly accounted for not only the safety of field staff, but also of related housing authorities and of course, the people who call HUD-assisted housing their home.

At this point, Carson paused to recall the precise numbers and allow for the appropriated rumination into the scope of operations at the Houston field office. “There are actually 48,534 families [affected by Harvey], and that’s not to mention the families involved in multifamily, which is another 20,971. That’s a lot of folks, who our folks are still in the process of getting a handle on.”

Texas HUD workers are impressive and energized in times of great need, Carson stated. And it’s an attitude the entire city seemed to adopt after Harvey.

“I’ve never seen anything quite like it, and it’s not just staffers, it’s neighbors helping neighbors. This is very different than like for Katrina where that was every man for himself. We’ve gone into some of these neighborhoods and everyone is hugging each other. ‘I’m over helping this neighbor and we’re going to clean up his stuff and after, they’re going to help clean up my stuff.’”

“I wish I could bottle that and sell it, so that when all of this is over, people continue to treat each other this well.”

A PERSONAL HISTORY

Benjamin Solomon Carson Sr. was born in Detroit in 1951. His father moved the family up north from Georgia and worked at an automotive plant in the Motor City. Most of his grammar school education took place at public schools there before his parents parted ways. Carson spent large portions of his childhood living in multifamily housing.

“Growing up, with a lot of economic deprivation, seeing what it did to people, I saw a lot of single women with children, and it was a terrible thing. We have had that fall upon ourselves. When my parents got divorced, my mother and us, we went out of the home and we found some relatives in Boston to stay with.

“And it was in a tenement, but at least it was a roof over our head. Just remembering how all this impacts people makes me want to eliminate homelessness. And I think we have the possibility to finally do that.”

By the fifth grade, Carson struggled with success in school, once declaring that his “D” in math was proof that at least he wasn’t getting any worse. His mother began to switch his television time with book study times and the more he read, the more he learned.

It became the catalyst for a major turning point in his life, as he recalls in his memoir, Gifted Hands: “The very kids who once teased me about being a dummy started coming up to me, asking, “Hey Bennie, how do you solve this problem?”

Racism persisted throughout his youth, sometimes overtly when street gangs called him racial slurs and sometimes more subtly, as when teachers “bawled out” white students for underperforming next to Carson. The affronts only fed his determination.

Carson served as director of pediatric neurosurgery at the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center, a position he assumed when he was just 33 years old, becoming the youngest major division director in the hospital’s history. In 1987, he successfully performed the first separation of twins conjoined at the back of the head, the medical term for which is called “craniopagus.” He also performed the first fully successful separation of type-2 vertical craniopagus twins in 1997 in South Africa.

Some could argue this history of running large, technical teams — he led 70 specialists in his first conjoined-separation surgery 30 years ago — make him the perfect candidate to run HUD. Healthy living depends on stable housing, after all, but some argue comparing the two sciences are like comparing apples to oranges.

But after studying Carson’s personal history, one realizes he is not easily defined as a surgeon-turned bureaucrat. In fact, his role as HUD secretary isn’t his first federal job.

Much is made of his surgical background, and rightfully so, but people may be surprised to learn Carson spent some time doing hard labor. In “Gifted Hands,” Carson explains that after his first year at Yale he took a position as a supervisor to a highway crew: They were “the people who pick up trash along the highways,” he writes. “The federal government set up a jobs program, mostly for inner-city students.”

Discipline was the toughest issue to confront, or rather the lack thereof. Carson explains the excuses were rampant: too hot, low pay, no recognition or satisfaction in one’s work — anything to try to get out of actually doing the work. While most crews of six men were bringing in around 12 bags of garbage per day, Carson’s crew regularly delivered between 100 to 200.

So what did he do differently? He understood that the men hated doing this kind of work, but even when pressed, he didn’t give a full explanation of his successful plan to his supervisors, lest they put an end to his practice. He understood that the men needed to be motivated to do more, and they also couldn’t stand picking up litter when drivers were simply going to keep throwing rubbish out of their windows regardless. He knew that for every moment those men stood out on that highway, they wanted to be somewhere else, so he came up with a solution to indulge that feeling.

If the men started before dawn, before it got hot, Carson would say that they were free to go home once they collected more than 100 bags of garbage as a team. If they finished in less than three hours, they still got a full day’s pay and the rest of the day off.

Soon it got to a point where Carson’s crew would start so early that they’d be finishing up, and returning back to the bag drop, just as the other crews were starting to arrive, around 9 a.m. This way, they could taunt the other crews and show off their superior results; it became more fun for his workers and Carson’s supervisors turned a blind eye even though they knew his crew was working in an unorthodox fashion. The results were just too good for the top brass to mess with.

“Some people are born to work, and others are pushed into it by their moms. But doing what must be done as quickly and as well as possible has been my strategy for everything, including medicine. We don’t necessarily have to play by the strict rules if we can find a way that works better, as long as it’s reasonable and doesn’t hurt anybody. Someone told me that creativity is just learning to do something with a different perspective. So maybe that’s what it is — being creative.”

However, leveraging creativity into success for the highway department led to Carson being offered the same spot the next year. But talk is cheap — the very next summer Carson remained unemployed, the promise of a job proved empty. The following summer proved more fruitful, as Carson assembled fender parts for Chrysler. He worked hard and loved it, and even earned a promotion in three months.

In short, the jobs came and went, private, public, corporate, but Carson’s resolve and ethic never wavered. The words of his beloved mother rang in his ears: “The kind of job doesn’t matter,” he writes in his memoir. “The length of time on the job doesn’t matter, for it’s true even with a summer job. If you work hard and do your best, you’ll be recognized and move onward.”

HIS PUBLIC POLICY

“The policies we’re developing are now aimed at developing human capital and not just aimed at putting somebody under a roof,” Carson explained. The secretary mentioned that society as a whole is becoming coarser in the way people treat each other and it’s wearing down the resolve of the nation as a whole.

In HUD’s capacity as the steward that provides a place to call home for some of the most vulnerable families in the nation, Carson feels this is where the best impact can be felt to the greatest extent.

One of Carson’s main initiatives is establishing “envision centers” of learning, especially for teenage mothers who, more often than not, end their educational trajectory once they give birth. New York City is seen as a potential spot for one of the first such centers where young, low-income parents can access day care while learning to code and “balance a checkbook or unclog a toilet,” the secretary told me. The project remains far from being piloted, especially considering recent cuts to HUD’s budget.

The plan, at least what we know so far, is that the centers will also offer U.S. Department of Education STEM concept videos, designed to help students learn pivotal concepts in science, technology, engineering, and/or mathematics.

But before he can fix the nation’s problem, Carson acknowledged that he needs to work on the operations within the Weaver Building to lay the foundation of future success.

“One of the things I’ve learned is you can have a whole bunch of good ideas, but if you don’t have an operator, nothing is going to happen.” And when it comes to his current policy, as when the administration cancelled plans to reverse the Obama-era decision to do away with the FHA “life of the loan” insurance premium, Carson had a quick response.

“Ask yourself, why is it there? Well, obviously, it’s there to help create a backstop that you need to enter the program. When we’re talking about the FHA, we’re talking $1.3 trillion [emphasis his] in taxpayer money that has to be protected. A few years ago we had to go to the Treasury and get $4.7 billion; I don’t ever want to see that under my watch.”

Carson added that he wants to get to a place where policies are being enacted because they have been discussed at length and they are the solutions that make the most sense in the long run. He’s not interested in short-term fixes to gain political brownie points, as his move on reverse mortgages proves.

After months of considerations, HUD finally changed the requirements around its reverse mortgage program, announcing plans in late August to raise premiums and place tighter loan limits.

The government ’s Home Equity Conversion Mortgage program has long faced scrutiny due to the high risks associated with the loans. While improvements have been made on it, it still is one of the most volatile parts of the Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund, which is the Federal Housing Administration’s flagship fund.

The program, created for seniors aged 62 or older who are still living in their homes, allows seniors to withdraw a portion of their home’s equity. If FHA backing is for someone’s first home, HECM is for their last home.

For some older homeowners that are potentially in need of additional income, a reverse mortgage allows them to take the equity out of the house through lump-sum withdrawals, regular payments or a line of credit.

This FHA/HECM combination fully exemplifies what HUD stands for in this country: the loan bookends of either side of our lives. But neither should proceed with a mobility of purpose above an abundance of caution, in Carson’s mind.

“Reverse mortgage is an excellent idea for a lot of people to let people age in place, but when it was thought of, people were taking huge chunks of money out in the beginning and continuing to take out large chunks after that. So we fixed it and we changed the rules,” Carson said.

“It goes back to the same principle we talked about: protecting the taxpayers, protecting the next generation. The next generation can’t be paying for the excesses of this generation.”

So his role is two-fold: preserve the vision of HUD while providing a level of corporate responsibility. Carson wants to add a CFO, CIO and COO, to help balance these two edicts. And he thinks he has the talent to do it; meaning these roles could be filled once all of his undersecretaries fully move into their positions. There’s some progress to report on that front, as his main No. 2, Deputy Secretary Pam Patenaude recently sailed through her Senate confirmation.

“The whole purpose is running things like a business instead of a bureaucracy and basically we’re forming it from the bottom up. We’re talking to the people who have been here 10, 20, 30, 40 years getting their ideas, talking to people in the field getting their ideas, and taking that to our senior staff to come up with things that actually make sense.

“Again, the purpose now is to develop people. Housing is only a part of the development of the human capital. Of course, now we define successes in public housing not by how many people get into it but how many people get out of it.”

Dealing with complicated constructs and lifting heavy loads with a delicate touch is a place of comfort for Dr. Ben Carson. You could argue that it’s not unlike being a neurosurgeon, but a better understanding is to concede it is more like being Ben Carson. Understand that for all his life’s work, he’s still a learner as much as a teacher. He still looks upon the world with a gaze of wonderment. Be it the slums of Boston, or the grey, wet Washington morning, or the artwork adorning his office — to Carson, life is something beautiful to behold.

As the interview transitions into a photoshoot, Carson suggests to the HousingWire photographer, “be sure to get the pretty Italian painting in the shot,” referring to the framed landscape on the wall above him.

Indeed, it’s not just an Italian painting, but a depiction of Rome, with the Castel Sant’Angelo occupying the foreground in front of a shining Vatican. It’s a fitting observation: on one end the Vatican symbolizes salvation, and the Castel once served as a fortification the pope could retreat to when Rome would come under siege. As of now, Carson sits in a place of comfort, time will tell if he will need the fortress.