Housing economists are at a near consensus that the U.S. housing market is softening, but bull markets might be more likely than bear markets over the coming decades.

Lately, it seems like the roof of the housing market might cave in. Major indicators point to a significant slowing in the market. For instance, the CoreLogic Home Price Index fell for six straight months, with October data showing only a very modest increase. Existing home sales also fell for six consecutive months with only a small rebound in October. What’s more, new-home sales dropped 12% on an annual basis in October, housing starts are down approximately 7.9% from their post-recession peak in January 2018 and the month’s supply of new homes is now at an 8.5-year high. As such, it is understandable why some might think that the housing market cycle is coming to an end.

While it’s looking like the housing market peaked last year, there are reasons to remain optimistic about housing. First, broad and deep troughs in housing prices are the exception, rather than the rule, to long-term price trends. Second, housing inventory struggles to keep pace with demand. Lastly, the demographic structure of the United States should continue to support prime-household growth over the next two decades.

While it’s looking like the housing market peaked last year, there are reasons to remain optimistic about housing. First, broad and deep troughs in housing prices are the exception, rather than the rule, to long-term price trends. Second, housing inventory struggles to keep pace with demand. Lastly, the demographic structure of the United States should continue to support prime-household growth over the next two decades.

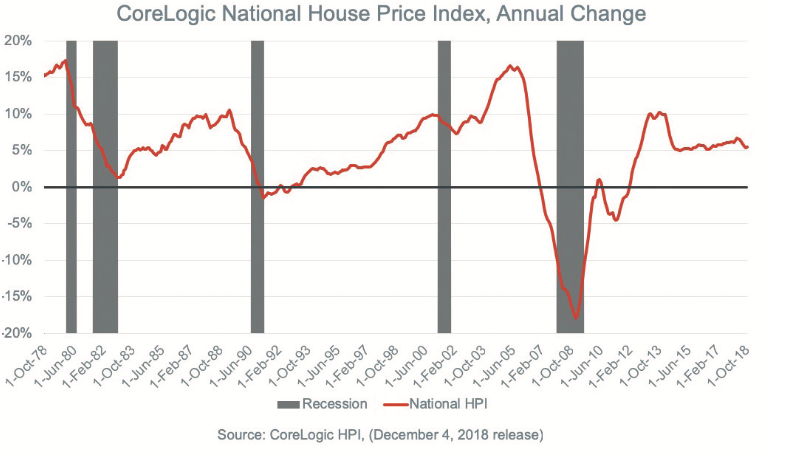

First, let’s look at historic trends of home-price growth. The Great Recession brought substantial devaluation to the housing market because it led to sustained home-price decline. However, persistent periods of declines aren’t common during recessions. For example, prices grew 6.6% over a nine-month period during the Dot-Com recession in 2001. During the 1980 and 1981 recessions, prices grew by 6.1% and 3.5%, respectively. In fact, just two of the past five recessions brought decreases in home prices.

There was a 1.9% drop during the 1991 recession, and, of course, the massive price drop during the Great Recession: a 19.7% decline during the recession itself, and a 33% crash measured from the home-price peak to trough. Though the sample size of recessions discussed here is small, combined they put the chances of negative price growth during the next downturn at 40%.

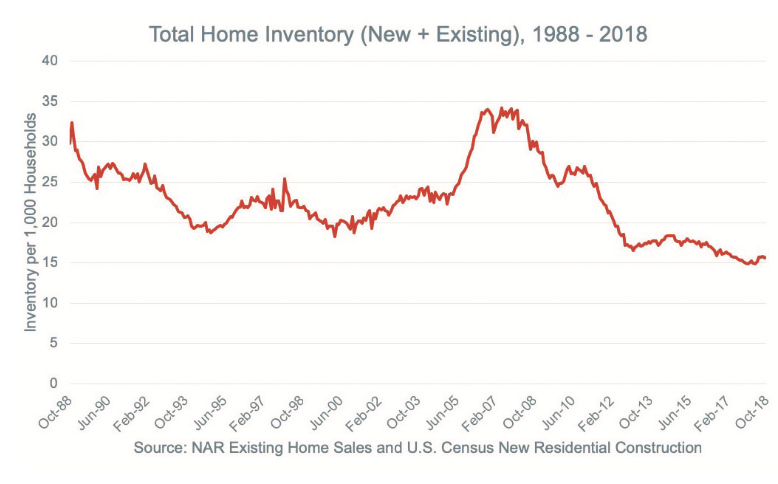

Second, a structural shift in U.S. housing inventory may help set a high floor for home prices over the next few decades. Looking at historical trends of the two components of housing inventory – new and existing homes for sale – it’s clear there’s a substantial lack of inventory relative to historic norms. Total single-family inventory, the sum of newly-built and used homes, sits at just 15.7 homes per 1,000 households. This is up slightly from the record low of 14.9 set in  December 2017.

December 2017.

The fact that we’re at historically low inventory is important because it means we’re in a very different supply environment compared to the massive run up in inventory that appeared before the onset of the Great Recession. This sharp increase in supply exacerbated price declines as demand waned. Because inventory is so low today, prices are unlikely to fall sharply if the market continues to slow and sets a high platform for prices to rise during the next expansionary period.

Third, the demographic structure of the United States looks like it could support strong growth of prime-age households (households with individuals between ages 35 and 54) through 2035. Currently, just under 46% of the U.S. population is under 35, and this cohort has historically low homeownership rates compared to older generations. As this cohort ages and gets their housing-market sea legs, we should expect them to form new households as they enter into their peak marital and child-bearing years.

The Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies estimates Millennial households are expected to grow from about 18 million households in 2018, to 39 million in 2025 and 50 million by 2035. Regardless of whether their aspirations for homeownership materialize, this surge in household growth will continue to support both the owner-occupied and renter-occupied sectors of the housing market. Furthermore, there are recent signs that young households are starting to own more homes – households under 35 have been the primary driver of the increasing homeownership rate over the past year.

While these factors provide points of optimism for the housing market, it is important to recognize important headwinds that might dampen long-term prospects for a healthy owner-occupied housing market and its positive contributions to gross domestic product.

For starters, the same forces that support long-term price growth, namely low existing inventory and sluggish homebuilding, could put downward pressure on the ability of younger households to buy homes. Slow growth of such owner-occupied households matters for GDP growth in two ways. First, the multiplier effect on consumer demand is likely larger for new owner-occupiers than renter households. In other words, new homeowners tend to buy more household goods for their home than new-renter households.

Second, since owner occupants are more likely to make substantial additions and alterations to existing homes – and reside in homes that are larger or have more amenities – future contributions to GDP from single-family homebuilding and home improvements will be less.

The other headwind is what I might refer to as “animal timidness,” which is the opposite of the “animal spirits” that John Maynard Keynes coined to describe the human emotion that drives consumer confidence. Though most recessions have benign effects on the housing market, consumers that lived through the collapse of the housing market might develop recency bias which could affect behavior during the next recession. Both Gen Xers and Millennials, who saw their first major recession end with the bottom falling out of the housing market, could pull back their desire to engage in the housing market should the economic cycle trend downward.

While it’s unlikely that animal spirits are driving demand today, there is at least a moderate risk that younger households will exhibit animal timidness during the next correction. Given their cohort size, apprehension among these buyers is something to watch out for; it may lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy that housing markets don’t weather recessions well.

The takeaway here is that the housing market appears to be in good shape to weather a downturn, and long-term prospects for growth look solid through 2035. Beyond 2035, an aging population introduces some degree of systemic risk to growth in the housing market and broader economy and, as such, is something economists and industry players alike should keep a close eye on.