While the first four and a half months of 2023 had significantly more housing demand than we expected coming out of the ice-cold fourth quarter, the real story of the year is the restricted supply of homes to meet that demand. Low inventory continues to be a major issue for the market, and we’re seeing signs that there’s no end in sight.

What’s normal for this time of year?

Normally in the spring — the pandemic years notwithstanding — we see inventory rising as sellers put their homes on the market readying for the summer home-buying peak. In typical years, the low point for homes on the market is mid-February. This year that low point was 10 weeks later, in late April as the quantity demanded exceeded the quantity supplied for homes during the entire first quarter.

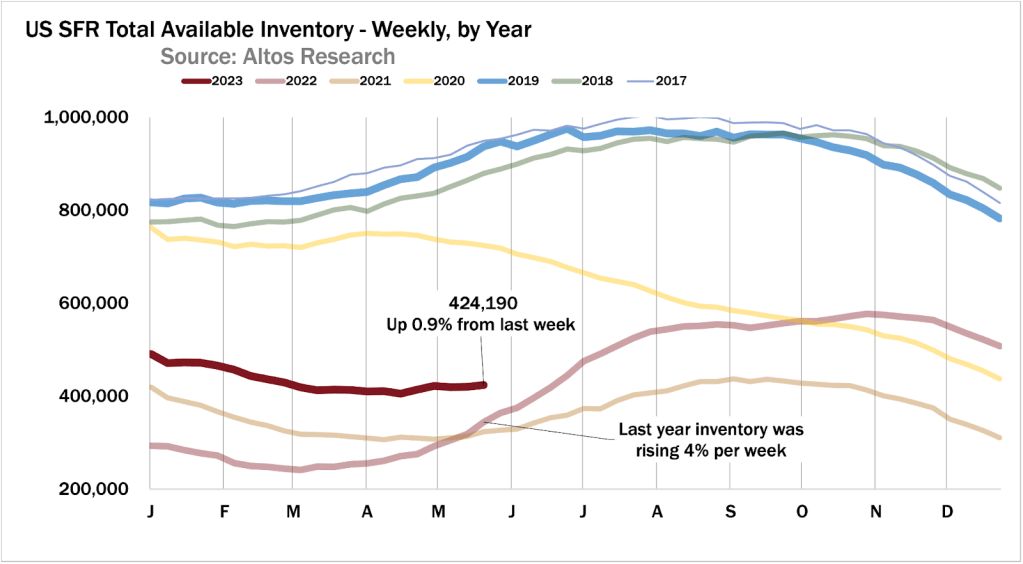

In this chart we’re showing the inventory curve of unsold single family homes weekly for each year. Each line here is a year. The pandemic years’ inventory are the lines at the bottom. From May 2020 through March 2021, the market was characterized by few sellers and ravenous buyer demand. You can see how last year inventory started rapidly increasing in the second quarter as mortgage rates rose. That’s the light red line. Later in 2022 inventory had a second burst of inventory growth in September, which was very unusual, and was a reflection of how dramatically homebuyer demand slowed as mortgage rates spiked over 7%.

As of mid-May 2023, there were only 424,000 single family homes on the market across the country. The lowest point was officially in mid-April. Available inventory of homes for sale is starting to inch up 1% per week now. Contrast that with the same period in 2022, when inventory was climbing as much as 6% weekly.

Why is inventory so restricted this year?

The first half of this year has seen significantly more demand than we expected, and fewer sellers, so inventory has fallen. It’ll take sellers to emerge, or buyers to drop out, for active inventory to finally rise again. We saw last year how abruptly and completely buyers could freeze when the tides turn against them.

This article is part of our ongoing 2023 Housing Market Forecast series. After this series wraps, join us on May 30 for the next Housing Market Update Event. Bringing together some of the top economists and researchers in housing, the event will provide an in-depth look at the top predictions for this year, along with a roundtable discussion on how these insights apply to your business. To register, go here.

With the debt ceiling crisis in Congress, we now have a new wrinkle that could slow the housing market. Mortgage rates have climbed to 7% for the first time since October as the uncertainty of the potential default looms over us. Home buyers are sure to feel this cost pain. If it lasts for very long, inventory will rise.

Inventory of homes could come from three possible seller sources: existing homeowners who trade up or down; investors who are selling to perhaps de-leverage or unload newly unprofitable properties; or distressed / forced sellers — usually people out of work because of a slowing economy. None of those groups has emerged as home sellers yet this year.

With high interest rates making it harder for current homeowners to trade up (or even down), especially when they likely have a low mortgage on their current home, most of them just aren’t interested in moving. But even those who are moving, due to life events for example, are often holding their existing home as an investment property, even when they buy the next home, because they’re locked in at a low rate. Result: no new inventory.

Why aren’t investors selling even as mortgage rates have climbed and made some properties less profitable? In addition to cheap financing, investors who own rental properties have enjoyed another powerful windfall in recent years: low levels of unemployment leading to rising rents. Most investors, especially the mom-and-pop owners of 1-4 homes which make up 90%+ of all real estate investors, have fixed-rate financing.

So when rates rise, the next investment becomes more expensive and less desirable. Owners of big apartment buildings are more likely to have variable financing, and we’re starting to see some of those owners be caught in unsustainable debt. That impact of commercial real estate owners has not been seen in the smaller investors market at all.

Americans are still near record levels of employment, so there has been no notable downward pressure on rents. Even if it’s harder to unload a rental property than it was 18 months ago, the vast majority of those deals are still very profitable. Result: no new inventory.

This record level of employment also means that we have record-few mortgages in any stage of delinquency right now. Based on this measure, American homeowners are in really strong financial shape. They’re well-employed, with cheap mortgages, and a lot of equity. Unless that equation dramatically, we won’t see inventory from distressed sellers.

What’s next?

The question for the rest of the year is how quickly the dark red line on the chart above climbs. Does demand weaken again like last year? That’s going to be a question of mortgage rates and the economy. Does the debt ceiling crisis break worse or get resolved? Do we have big job losses coming? Do we have banking crises or other shocks coming? Even the uncertainty itself is a risk to derail housing demand from here.

If these major shocks are held at bay, this year’s curve will look more like most of the years on this chart, and we’ll end the year with under 500,000 homes on the market again — staying in this pattern of incredibly restricted supply.

If the economy tanks hard, then the curve could pick up quickly like last year. This is a real possibility, but there’s no indication anywhere in the data yet that any surge of inventory is imminent.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of HousingWire’s editorial department and its owners.

To contact the author responsible for this story:

Mike Simonsen at mike@hwmedia.com

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Brena Nath at brena@hwmedia.com