The Federal Reserve will hold another meeting this week, where everyone assumes we will get another 75 bps rate hike. The question is: how many more rate hikes are left? And, once they’re done hiking rates, will the Fed need to keep rates high because the consumer balance sheet looks so good?

Over the weekend, The Wall Street Journal brought up this point — that the Fed is mindful that household balance sheets are much better now due to the excess savings built up during the COVID recovery and they might need to raise rates again or keep them high to trigger their job loss recession to fight inflation.

From the WSJ article: “U.S. households still have around $1.7 trillion in savings they accumulated through mid-2021 above and beyond what they would have saved if income and spending had grown in line with the prepandemic economy, according to estimates by Fed economists. Around $350 billion in excess savings as of June were held by the lower half of the income distribution, or around $5,500 per household on average.”

For my economic work, household balance sheets were better during the last expansion than prior to the housing collapse. This was key to the recovery going into the COVID-19 crisis and getting out of that brief recession because we didn’t have a credit bubble that needed deleveraging.

This time is much different than what we saw at the century’s start. This is one of the pillars of the COVID-19 recovery model I wrote on April 7, 2020 and why I created the phrase the “forbearance crash bros” in the summer of 2020, because I knew household balance sheets were good this time around.

Major consumer protection debt laws passed were key

One of the unsung heroes of the most prolonged economic and job expansion ever recorded in history was the passing of the 2005 Bankruptcy Reform Act and the 2010 qualified mortgage rule under Dodd-Frank. Both these laws paved the way for more responsible lending and a more responsible consumer.

In 2000, we saw a lot of credit stress in the system. As we can see below, the bankruptcy levels were extremely high before the bankruptcy law was passed in 2005. That law also facilitated a final big push by consumers to file for bankruptcy before the laws made it harder. Then we saw an uptick in people filing for foreclosures and bankruptcy during an economic expansion from 2005 to 2008. After all that credit stress, then the job loss recession happened.

As we can see above, none of this happened in the expansion from 2010 to 2020, as credit standards were much better. Now, over time, we should get back to pre-COVID-19 trends in foreclosures and bankruptcies, but as you can see, the consumer is in much better shape because the credit system is in much better condition.

All my six recession red flags were raised toward the end of 2006, and the recession didn’t start until later in 2008. This year, I raised my sixth recession red flag on August 5, so I am on recession watch now.

The Federal Reserve is trying to cool inflation by slowing the economy down and raising the unemployment rate. When the Fed says they may need to keep rates higher for longer, I believe that’s them talking tough, as they can fall back on the fact that the labor market is still solid and household balance sheets are good.

This, of course, only works if the employment data stays firm. I believe the Fed can talk tough as long as jobless claims remain below 323,000 on the four-week moving average. Once those levels break, then a lot of things change. So, it will be critical to hear what the Fed thinks of the economy now and going out with rate hikes.

Housing already in a recession, but no credit stress

During the build-up to when the housing bubble burst, housing was getting noticeably weaker on many fronts. What was more damaging was that people were filing for foreclosures before the job loss recession even happened. Currently, the housing market is in a recession: sales, production, jobs and incomes are all falling in the housing sector. This is something I talked about on CNBC a few months ago. But this is a traditional housing recession, this is not a credit bust like we saw during the housing bubble years.

The Federal Reserve wants a housing reset. They know housing is in recession already, but they don’t care because they don’t see a credit bust or a job loss recession yet. Total inventory in America grew from 2000 to 2005 while demand grew. The FOMO demand (fear of missing out) credit boom from 2002 to 2005, as we can see below, has not happened in the last 10 years.

Purchase application data is below 2008 levels today. However, total inventory levels today are below 2019, 2014, 2007, 2005, and 2000 levels because homeowners are in a good place financially. In 2005, we saw a massive spike in inventory during an economic expansion, and then the job loss recession happened in 2008.

While the economy was still in expansion mode, inventory rose from 2.5 million in 2005 to over 4 million in 2007, with foreclosures and bankruptcies rising since then. Today, we are at 1.25 million total inventory, according to NAR, and household balances still look good.

Now, a job-loss recession can change this narrative. However, unlike the credit stress of 2005 to 2008, we are back to traditional late-cycle lending risk with primary homeowners. Those homes with a meager down payment that don’t have excellent FICO scores or a lot of reserves would be the high-level risk for future foreclosures.

This is why I am very mindful of recent 100% loans that some banks are offering. So while the Fed might be monitoring the housing recession to see how bad it gets, they’re not worried enough to start talking about lower rates or buying mortgage backed securities to help housing grow again.

Consumer balance sheets and debt payment levels are healthy.

Then there is the consumer balance sheet, which still has between $1.5 to $1.7 trillion in excess savings post-COVID-19 and $350 billion in the hands of lower-income households, which makes the Fed feel better about their rate hikes. From the Fed: ,

The Fed feels good about household debt payments as a percentage of disposable incomes — this is close to all-time lows. After the housing bubble crashed, a lot of household debt got deleveraged through foreclosures, short sales and bankruptcies. What was left was fixed long-term debt cost that benefitted from three refinancing waves, driving down the total cost of debt as a percentage of disposable incomes.

Homeowners look great with their nested equity positions; with price gains over the last several years homeowners now have a lot of equity built in. Also, homeowners have been living in their homes longer and longer, so their nested equity position has improved over time. And, more than 40% of homes in America don’t even have a mortgage.

On top of all this good news for homeowners, their mortgage payment as a percentage of disposable income look excellent. We have had three refinance waves since 2010, which created better cash flow for homeowners, meaning the bulk of the households with the highest levels of nominal debt load look excellent. So you can see why the Fed feels a bit more confident that the economy can take these rate hikes to break down inflation and why inflation might have more legs because we don’t see credit stress in the system.

This is a big reason why the credit scores of homeowners have looked solid post-2010 and should always look solid as long as we don’t ease lending standards.

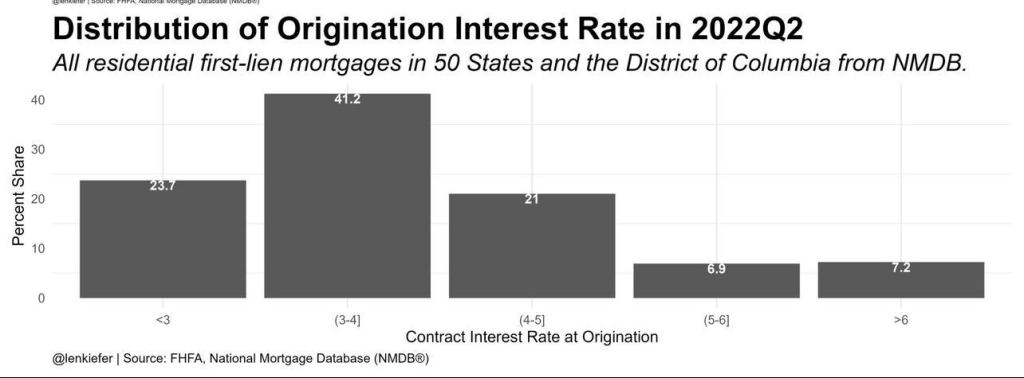

Another good data line from Len Kiefer, deputy chief economist at Freddie Mac, is the distribution of mortgage households and their rates. As you can see below, nearly 65% of households have rates between 2%-4%, and 85.9% have rates of 5% and below.

With the Fed meeting this week to raise rates again, the speculation is what happens after. Are we getting closer to the end of the Fed rate hike cycle? At that point it will be all about the economic data.

I don’t see the Fed changing their tune on rate cuts until the labor market breaks. I believe they will use the strength of household balance sheets to justify hikes because they think rates need to stay higher for longer. However, with all the rate hikes in the system now, once Americans start losing their jobs, the Fed’s tone will change.

It will be hard for them to justify high rates when Americans lose their jobs, no matter how good the consumer looks on paper. Now that all six of my recession red flags are up, the only data line I am focusing on is the labor market. Once that turns, the job-loss recession is in.

That should help the Fed fight against inflation since they believe a higher unemployment rate will mean less wage growth and less inflation. We are getting into a fascinating period with the Fed, their talking points and the economic cycle. Last week I made a case for lower mortgage rates in 2023, but that was based on the bond market. For the Fed to start rate cuts, they need to see a job loss recession.