One of the distinctive features of modern economies is constant measurement.

A consequence of many interrelated factors, constant measurement is very much a product of capitalism.

Guest Author

However, in the American economy today, we have gone far beyond simple measurement that’s connected to the main levers of economic planning and growth.

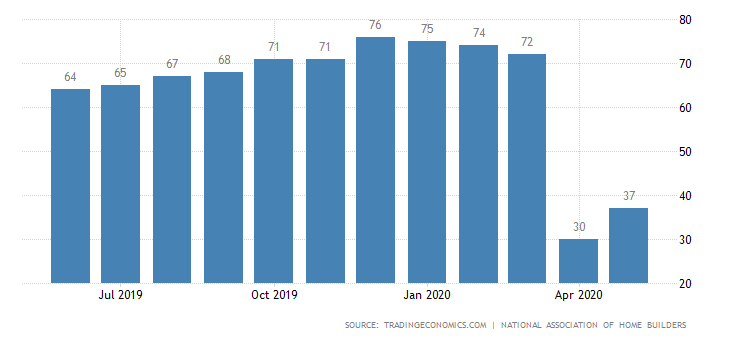

This is why most indices should be understood to be very thin slices or a larger and often internally contradictory reality. Not to pick on anyone specifically, but take for instance the NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Marketing Index (HMI) that is based on monthly surveys of NAHB members and “is designed to take the pulse of the single-family housing market.”

It is too difficult in this short article to get into the details of the methodology or to examine the historical numbers. But it is worth looking at the recent measurements:

While the numbers were incrementally moving lower in the first three months of the year, after hitting a “local maximum” in December 2019, it crashed in April 2020 only to recover partially in May 2020.

We all know the reason for the crash: the COVID-19 pandemic. But we should be clear – the reason doesn’t matter.

What does matter is that the “confidence” that was measured (and invested in) in the months and years preceding this precipitous crash was unfounded. The excess investments, decisions and prognostications made based on this false confidence were inefficient, unscientific and likely economically damaging.

The point here is not to suggest that this particular index is worse than others, but that these indices don’t just reflect sentiment. Through their very measurement and marketing, they encourage actions and lead to large investment decisions.

As with the stock market and with oil prices, this confidence index does not inspire confidence when you apply even the slightest pressure to it. Indices like this are not prophetic, other than in the minor self-fulfilling prophecies they create.

While we cannot abandon measurement, we also should not have a theological view of economics or measurement. We need to have the discipline to understand that data offers us a partial snapshot into a temporal reality and does not offer a preview of the future.

What we need to do, as a partial corrective to the current approach, is to assemble a group of sociologists, mathematicians, data mavens, AI engineers, policy experts and working people to develop flexible frameworks that are “aware” of their own fissures and shortcomings.

We can’t afford to continuously double-down based on limited data or to “put it all on red” just because we feel “confident.”

We owe it to the industry and to the population of the country to approach this with more humility, a quality too often foreign to our anointed economists.