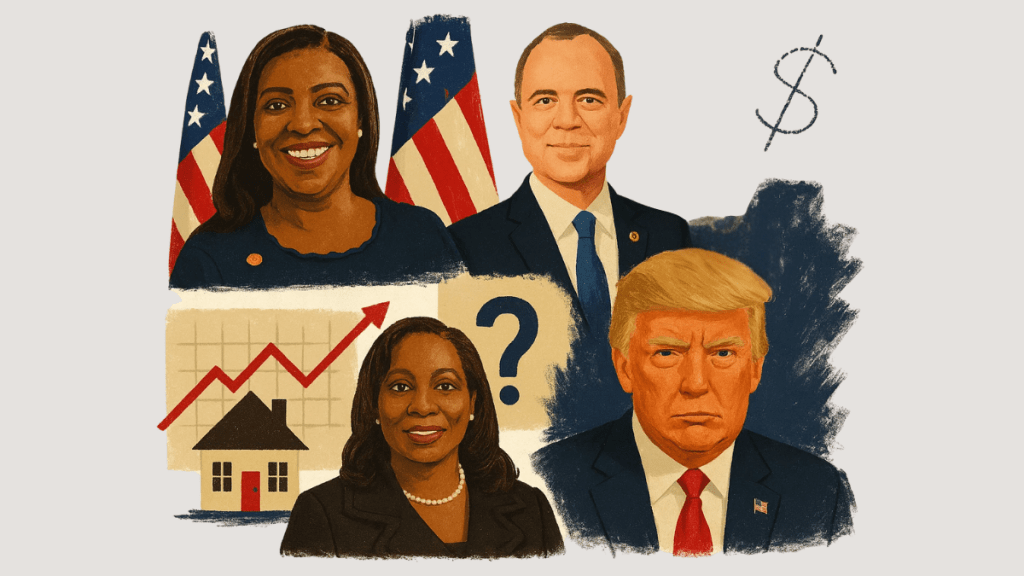

Occupancy fraud has become a catchphrase since President Donald Trump raised allegations against Democratic Sen. Adam Schiff of California, New York Attorney General Letitia James and Federal Reserve Governor Lisa Cook. But behind the political noise, how much of a problem is it in today’s mortgage industry?

Industry experts say the scheme is far from new. The practice — when a borrower pretends they’ll live in a home to secure lower rates meant for primary residences — was common during the housing bubble of the 2000s. It still exists today but represents only a small share of applications.

The numbers may be smaller, but the risks are real.

“We’re on the tail end of the buying season, and we are seeing potential indications of occupancy fraud to investigate it — but it wouldn’t be anything more significant than what we have come to expect just being in a higher volume set of months,” Amanda Tucker, chief risk and compliance officer at Atlantic Bay Mortgage Group, said in an interview with HousingWire.

Atlantic Bay reviews all origination files prior to closing to flag potential issues. That includes borrowers who are purchasing in different state from where they currently live, or those refinancing homes listed on short- or long-term rental platforms. The lender then works directly with borrowers to clarify their true intent for the loan.

“I’ve been doing this 22 years, and it’s always been a part of our compliance framework,” Tucker added.

A 2023 study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia found that occupancy misrepresentation peaked in 2006, when nearly 7% of loans showed signs of fraud. Even after the housing crash, the problem persisted as between 2% and 3% of loans in the post-bubble period were flagged.

Researchers analyzed more than 584,000 loans from 2005 to 2017, focusing on investors who purchased more than one home as “owner-occupied” within a year. These borrowers defaulted at a 75% higher rate than other investors and were riskier because they had lower credit scores, higher loan-to-value (LTV) ratios and additional debt.

These loans were sold to the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, held in bank portfolio or bundled into private securitizations. For lenders, the risk of overlooking occupancy misrepresentation is costly as investors can initiate buyback requests.

The standard deed of trust a borrower signs at closing requires them to occupy, establish and use the property as a primary residence within 60 days of the closing date and continue to occupy it for at least one year.

Back in the spotlight

The current economic backdrop is adding pressure. Higher mortgage rates and rising homeownership costs make it tempting for some borrowers — often sophisticated ones — to stretch the truth in exchange for a slightly better rate or a higher LTV.

Primary residences are seen as lower-risk loans than investment properties, which are more likely to default if a borrower has financial trouble, and that creates an incentive for misrepresentation.

“As rates are higher, it probably creates more pressure in the system for people to mislead or lie to somebody, because it’s harder to afford the house, especially an investment property,” said Troy Garris, co-managing partner at Garris Horn LLP.

Data reflects this tension. Cotality’s Mortgage Application Fraud Risk Index shows occupancy fraud risk rising through 2023, plateauing in 2024 and beginning to ease in 2025.

In the second quarter, it fell 0.9% year over year. Overall, one in 116 applications — or 0.86% — showed signs of potential fraud of any type in Q2 2025, up 6.1% from the previous year as purchase activity remains strong.

“There’s been a lot of news in 2025 about occupancy fraud, and it’s still one of the highest confirmed fraud categories, according to Fannie Mae data,” Matt Seguin, the company’s senior principal of fraud solutions, in a statement. “Cotality’s data is based on applications and often a leading indicator of a change in risk. In this case, occupancy fraud risk, while still prevalent, seems to have leveled off and even begun dropping slightly.”

Fannie Mae’s August 2025 post-closing fraud report shows occupancy fraud increasing over time — from 10% of findings in 2020 to 29% in 2024, making it the second most common issue among 2024 vintage loans. The most frequent scenario involves investors claiming primary residence status for a property.

Seguin suspects Fannie Mae saw that increase until 2024 because its data on closed loans lags behind Cotality’s. It takes a while — potentially years — for the fraud to be found, he said.

“There are a couple of reasons this issue is in the spotlight — the biggest being politics,” said James Brody, a founder and managing partner at Brody Gapp LLP. “But artificial intelligence is also being deployed to detect fraud more effectively on the front end.”

The real implications

Attorneys said the main challenge with occupancy fraud is proving the borrower’s intent. Life events such as divorce or a new job can make a primary residence application in one state no longer accurate. This can be verified through supporting documents like tax returns, bills and job offer letters.

“Both the law and the the most standard mortgage origination agreements require a duty to disclose any change of circumstance,” said Scott Harkless, a founding partner of Brody Gapp LLP.

Fraud can also involve real estate agents, loan officers and others who participate in the transaction. But Harkless noted that it’s rare for lenders to make criminal referrals. It’s a felony under the statute and the penalties can be severe.

Harkless added that the high-profile cases currently in the news are a reminder for borrowers to take it seriously. In addition, the industry likely benefits from this attention so that it continue to have clean, reliable mortgages.

According to Garris, some of the high-profile cases are drawing more attention, and quality control teams may be scrutinizing these loans more closely. The likelihood of additional resources, systems and AI solutions being deployed will increase the ability of investors and regulators to identify issues, he said.

This matters for maintaining a healthy system that borrowers and investors can trust. The issue also has a systemic impact: When borrowers access homes through occupancy misrepresentation, other buyers may be blocked from purchasing their first homes.

“It would be interesting to have an industrywide, consistent review of data,” said Tucker of Atlantic Bay. “The challenge is, if you say, ‘Well, the loan is performing and they’re paying, do we really care if they have a lower rate?’

“Oftentimes, that rate differential can make the difference for a first-time buyer or someone truly intending to purchase their dream home. That borrower can lose out in the competition.”