In the days following the 2016 election, business leaders across many industries were hopeful that the new president would make good on his promise of widespread deregulation. Banks and other financial institutions, weighed down by the myriad federal regulations spawned by Dodd-Frank, were especially optimistic. Here at last was the relief they had been looking for.

Or not.

In fact, the Trump administration’s efforts to hack off significant parts of the federal regulatory monster has rallied state attorneys general to the cause of consumer protection, complicating the already expensive and confusing process of compliance.

Although the Trump administration has achieved some loosening of federal regulations, it has done so haphazardly, creating uncertainty at every turn. Direction from the White House often changes on the fly, surprising even Republican leaders and the very loyalists charged with carrying out the president’s agenda.

And for all the promises to repeal Dodd-Frank, the bill that was passed by a Republican-controlled Congress and signed into law by the president in May falls far short of any actual rollback. While providing important changes for smaller financial institutions, it contained none of the other key provisions of the CHOICE Act.

“I think at a federal level what we’re seeing is no new regulations rather than material cutbacks of existing regulation,” said Larry Platt, partner at Mayer Brown.

“The enforcement of those regulations is lessened, but we do not expect enforcement to go away for clear violations of existing consumer credit laws and regulations.”

Meanwhile, all the big talk of repealing federal consumer protection laws has juiced state regulators to ramp up their own enforcement, multiplying the compliance risk for companies in the mortgage industry.

THE HYDRA OF STATE REGULATIONS

States have several avenues at their disposal to regulate state-chartered financial institutions: individual state banking commissioners who perform individual examinations of lenders, state banking commissioners acting in concert through multistate examinations, individual state attorneys general, and state AGs who collaborate in multistate actions.

Since the individual state banking commissioners are more focused on loan-level issues, the larger risk for lenders lies in the multistate exams.

“Those are on the upswing, and those can be problematic because the threat is that collectively they can revoke state licenses if companies don’t comply with demands,” Platt said. “There are not a lot of guardrails around multistate exams and there is a lot of concern in the industry with state regulators rounding up a posse and going after lenders where it’s hard to defend themselves.”

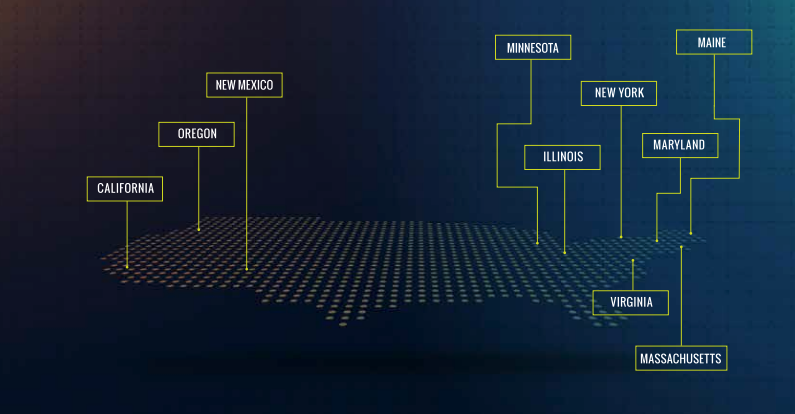

State AGs represent a similar danger. Individual states like California, Illinois, Massachusetts and New York have historically been the most aggressive regulators, but during the run-up to the financial crisis, something even more hazardous emerged.

“During the subprime years before the crisis hit, of all the four various types of state actions, it was the multistate AG actions that were the most intense,” Platt said. “What I’m seeing now is there will be — and have been — more state multistate AG actions.”

When Trump was elected after campaigning on regulatory reform, alarm bells started ringing in state houses across the country, galvanizing state AGs to shore up the protection of consumers.

And when the acting director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Richard Cordray, was replaced (in a still-disputed decision) by Interim Director Mick Mulvaney, that regulatory zeal went into overdrive.

In December, after Mulvaney was named to his role, 16 Democratic AGs wrote a letter to President Trump that made their position clear.

“As you know, state attorneys general have express statutory authority to enforce federal consumer protection laws, as well as the consumer protection laws of our respective states. We will continue to enforce these laws vigorously regardless of changes to CFPB’s leadership or agenda.

“As attorneys general, we retain the broad authority to investigate and prosecute those individuals or companies that deceive, scam, or otherwise harm consumers. If incoming CFPB leadership prevents the agency’s professional staff from aggressively pursuing consumer abuse and financial misconduct, we will redouble our effort as the state level to root out such misconduct and hold those responsible to account.”

That was a clear shot across the bow of the CFPB by some of the largest states, including California, New York, Illinois and Virginia, and they were careful to point out their ability to enforce not only state laws, but federal ones.

In April, after the CFPB issued a Request for Information on Bureau Civil Investigative Demands and Associated Processes, those same AGs doubled down, sending a letter to Mulvaney outlining their strong support for the bureau’s “historical and continued use” of civil investigative demands. From the letter:

“We strongly oppose any curtailment of the Bureau’s investigative authority, as it would significantly hinder the Bureau’s ability to fulfill its mandate of promoting fairness, transparency, and competitiveness in the markets for financial products and services…Nor do civil investigative demands exist only in the federal system.

“In California, for example, the Government Code empowers the head of each department in the state, including the Attorney General as the head of the Department of Justice, to issue subpoenas and to use other tools to investigate ‘all matters relating to the business activities and subjects under the jurisdiction of the department.’

“This grant of civil investigative authority has been crucial to the California Attorney General’s mission of protecting consumers and honest competitors and, when appropriate, prosecuting violations of state law.”

Interestingly, Mulvaney himself has acknowledged the important role state AGs play in regulation. Barbara Mishkin, writing for Ballard Spahr’s Consumer Finance Monitor, reported that at the winter meeting of the National Association of Attorneys General in February, “Mulvaney indicated that the CFPB will be looking to state attorneys general for ‘much more collaboration and much more leadership’ when deciding which enforcement cases to bring.”

But AGs aren’t the only ones carrying a big stick. The New York Department of Financial Services has been a fierce regulator of financial companies since its founding in 2011. Following Mulvaney’s speech in January pledging a “kinder and gentler” CFPB, the NYDFS Superintendent Maria Vullo vowed that her agency was prepared to step in to address the CFPB’s “troublesome policy shift away from consumer protection.”

“I am disappointed by the new administration’s sudden policy shift, which is clearly intended to undermine necessary national financial services regulation and enforcement,” Vullo said in her statement. “DFS remains committed to its mission to safeguard the financial services industry and protect New York consumers, and will continue to lead and take action to fill the increasing number of regulatory voids created by the federal government.”

Anybody familiar with the NYDFS’ history knows that Vullo’s statement is not an idle threat. In 2018 alone, the regulator fined Western Union $60 million, Goldman Sachs $54.75 million and Nationstar Mortgage $5 million. Even before the 2016 election, NYDFS was taking the lead in developing a robust cybersecurity law that was widely seen as the forerunner of a national standard (see sidebar on page 37). Where New York goes, other states soon follow.

President Trump was set to announce a new head of the CFPB at press time, but it’s unlikely that new leadership is going to change the equation very much.

For the mortgage industry, compliance with all of these regulations comes at a cost. Independent mortgage banks and mortgage subsidiaries of chartered banks reported a net loss of $118 per loan originated in the first quarter of 2018, according to the MBA’s Quarterly Mortgage Bankers Performance report. This is down from a gain of $237 per loan in the fourth quarter of 2017. That’s one reason some of the large banks have pulled back from the mortgage business.

“Regulators have a fundamental purpose to protect consumers. But in the residential mortgage market, nobody is making money, and many are losing money,” Platt said. “In part, that’s because of the cost of regulation and cutthroat competition. There’s no real private securitization market — everybody has to go through Fannie or Freddie or Ginnie — so margins are really, really low.

“It’s great that consumers are protected, but nobody is protecting the industry itself. How does it survive in an environment where it’s really hard to make money and the cost of compliance is not a variable expense?” Platt asked. “The question is whether the expenses imposed by federal and state compliance requirements are overkill for the benefits consumers receive.”

Unfortunately, growing regulation could have unintended consequences for the very consumers it seeks to protect: they may be completely safe from ever owning their own home.