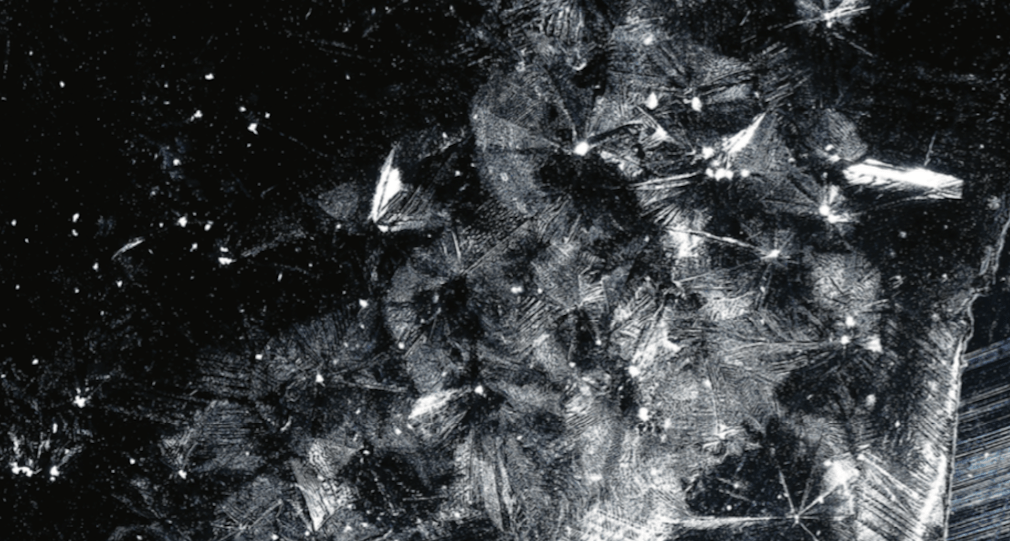

Compliance risk is a quiet danger, like crossing a lake that’s still in the process of slowly freezing over. Is the ice solid enough to hold your weight? What will happen when you put pressure on the weak spots? The only way to safely cross is to have a plan and go slowly, testing the ice before each step and looking out for cracks along the way.

Lenders gearing up for the implementation of new Home Mortgage Disclosure Act rules are in that process now, although with the deadline looming on Jan. 1, 2018, there are still lots of questions. In fact, compared to the sound and fury surrounding TRID, when it seemed every other conversation or article was counting down the days until the deadline (and then the deadline moved), the industry’s anticipation and preparation for HMDA changes seems eerily calm.

It’s possible that after a decade of adjusting to multiple business-changing regulations, lenders and other mortgage companies have become adept at incorporating new requirements into their processes. It’s also possible they have compliance fatigue. Either way, the updated HMDA reporting requirements represent a new set of risks that lenders need to pay attention to.

BIG CHANGES

The Home Mortgage Disclosure Act was enacted in 1975 and implemented by the Federal Reserve Board’s Regulation C to help prevent discriminatory and predatory lending practices. From its inception, banks and other lenders have provided data on the number of mortgage loans made, loan amounts, and various borrower characteristics, giving consumers, investors and government regulators a window into their lending process.

The act has gone through various updates, but the newest HMDA requirements are the most comprehensive yet, modifying the triggers for lender coverage, modifying the loans that are reportable and expanding the data that must be collected.

After a confusing array of triggers in 2017, for 2018 the triggers are much more straightforward: an institution will be subject to Regulation C if it originated at least 25 covered, closed-end mortgage loans or at least 500 covered, open-end lines of credit in each of the two preceding calendar years. The regulation originally set the threshold at 100 open-end lines of credit, but after negative industry feedback, it was changed to 500, where it will stay until 2020 before reverting to the lower number.

Under the new rules, the data points that lenders must collect more than doubles, from 23 to 48, and 20 of the existing fields are modified. Some of the new data fields were mandated by the Dodd-Frank Act, while others were added by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

NAVIGATING THE TERRAIN

Like all regulations before it, implementing the new HMDA requirements presents some significant challenges. One of the biggest is collecting information early enough in the loan process so that if the loan falls out, lenders don’t have to go back and try to get that information from the consumer. This might require updating policies and procedures to cover these scenarios.

“One of the lenders’ worst fears is that consumers will start going through the loan process and give enough information to trigger a reportable transaction, but then don’t get far enough to give all of this data,” said John Haring, director of compliance enablement at Ellie Mae.

“Going back to borrowers after they have withdrawn their application could feel invasive, since they have already told you they decided to go work with someone else. It’s hard enough to deal with happy homeowners who closed on their loan — good luck doing that on the loan you denied. If you missed your window of opportunity to get those 48 questions answered, getting them after the fact is extremely challenging.”

Another challenge comes from the expanded reporting on borrower ethnicity. In the past, if borrowers did not want to furnish their ethnicity, race or gender, lenders were required to determine those factors based on visual information and the borrower’s last name. Today, borrowers have more categories and subcategories to choose from in these areas, and for the first time, borrowers can choose more than one category for ethnicity, race and gender.

If borrowers don’t choose to identify themselves, lenders are still required to choose for them, using the visual cues/last name best-guess method. However, if a borrower chooses a category that doesn’t seem to fit with the lender’s visual inspection, the lender is not allowed to change that self-identification.

There are several potential problems with this system. Lenders will be judged on this information, yet there is no objective filter they can apply to the data provided. If the person appears to be of one race and gender, but fills in a different race and gender, how will that be evaluated when judging potential patterns of discrimination?

Surely the demographic data gathered by the lender will be matched up at some point with data collected through the borrower’s Social Security number and birth date, and found inaccurate. What happens then? And what is to stop borrowers or lenders from purposely reporting inaccurate data in these fields? If there is no objective standard to compare the data to, how could that information be proved to be false?

“One of the inherent challenges of fair lending is it assumes you are working off an accurate set of data,” Haring said.

In a further complication, the race and ethnicity sections also include free form fill-in-the-blank data fields that let borrowers define their race and ethnicity in a manner that seems to defy automation. Including those manual data fields introduces another area of uncertainty for lenders — and regulators.

“Here for the first time, the consumer, who previously had to select from a menu of choices, can now also write in their own responses. One of the things we just don’t know is how consumers are going to interact with that to provide their own response,” Haring said.

Helping borrowers navigate these new areas will require a hands-on approach by loan officers, who might need training on talking through potentially sensitive subjects.

“On one hand, the bureau is greatly expanding the amount of information they want to collect, and on the other hand, they are much more strict about the quality of that information,” Haring said. “The tolerance for error on HMDA reporting is extremely tight, requiring a perfect match of more information that is held to higher standards.”

In addition, poor data quality by itself can be the basis for action against lenders.

Speaking on a HMDA panel at the MBA Annual Convention and Expo in October, Mitchel Kider, chairman and managing partner at Weiner Brodsky Kider said, “Substance is important, but the accuracy of HMDA data is independently important as well. Does this [poor data quality] mean you have to resubmit? No, this means civil money penalties as well. It is a reflection of having a poor compliance management system in all other areas.”

Adding to lender anxiety, the portal they must use to submit HMDA data was released in beta version in November, giving lenders a scant two months to test their processes.

Technically, March 1, 2018, is the first deadline to submit HMDA data through the new portal, but lenders would like to be able to test the process ahead of that deadline.

“From the lender perspective, they aren’t going to feel like they are done until they have been able to test the process from end to end. The inability to do that causes uncertainty and doubt,” Haring said.

“I think the bureau looks at it differently, because the big push for them is Q1 2019, when they will be accepting files that have all the data points collected in 2018. For lenders, Jan. 1 is the deadline because they don’t want to have to be halfway through the year before they get access to the platform and then have to get additional data into loan files,” Haring said.

The bureau is also still deciding which of the new data points are going to be released to the public, accepting comments on the subject as late as November. At issue is how to protect borrowers’ privacy when so much is revealed in the new reporting.

As Richard Andreano noted in an article published by Ballard Spahr’s Consumer Finance Monitor in September, “there are concerns that by combining the current publicly available HMDA data with other data sources, the identity of each applicant can be determined. As the applicant’s income is one data item that is publicly disclosed, there is a concern that the income of individual applicants can be determined.”

In response to that concern, the bureau has proposed releasing some data points as ranges, including ages, loan amounts, property value and debt-to-income ratio.

Another worrisome area is the security of all this confidential data stored by the CFPB. In 2017, the CFPB’s Office of Inspector General identified “ensuring an effective information security program” as the CFPB’s most significant management challenge, one that is now even more important.

INCREASED RISKS

In an overview of the new HMDA requirements, the Mortgage Bankers Association outlined three areas of greatest impact to the industry: extensive implementation costs, privacy and data concerns, and increased litigation risk. That last one is perhaps the one keeping executives up at night.

“HMDA has been a major source of fair lending claims in the past, and the new data will allow greater analysis of application and loan data to evaluate impacts on protected classes. While HMDA’s purpose is to shine light on lending practices, data can be misused to present unfair claims-forcing costly litigation defense, and/or settlements and causing significant reputational harm,” the MBA wrote.

Indeed, the data collected and stored in such a tidy digital package broadcasts a siren song beckoning regulators to find everything they need in one place. In the past, HMDA reporting could trigger a fair lending review, but did not contain enough information on its own for regulators to determine discrimination. With the HMDA changes, the data will provide a complete picture for regulators, and lending pattern outliers can easily trigger an investigation.

“Your lending practices are about to become a wide-open book,” Kider said. “When there is more information available to the public and to regulators, there will be a lot more scrutiny and potential liability.”

“Now, all that data is available in a consistent electronic format and it will be very easy for others to compare you to peers, to drill down to specific information that was more difficult to obtain before,” Kider said.

The new data includes pricing information, origination charges, discount points, lender credits, interest rates, combined LTV ratio, credit score and DTI ratio. Analyzing those data points reveals a lot about lender practices, including what kind of loan programs they offer to different borrowers.

Maurice Jourdain-Earl, managing director at ComplianceTech and another panelist at MBA, pointed out that with this library of data, regulators will be able to more easily identify peer lenders with similar business models so that they can compare outcomes.

“All of the data is going to be there and available to do these comparisons,” Jourdain-Earl said.

“This is a more granular level than has ever been exposed before,” Haring said. “How is that information going to be used, and what is the risk to the lender if the data is considered outside of context that may or may not be accurate?”

And for the first time, that risk extends all the way to the individual loan officer who originated the loan. Because the NMLS number is part of the data collected, regulators can scrutinize even individual patterns of lending.

“Historically, HMDA and fair lending complaints are leveraged against institutions, because all of the information is gathered at an institutional level. With this new information, what will be interesting is whether that opens the door to actions against not only institutions, but against a single employee,” Haring said.

SILVER LINING?

Despite the challenges and risks inherent in the new HMDA rules, there is an upside for lenders willing to use the data to improve their process. Gaining better insight into their own lending patterns means lenders can address any issues ahead of regulatory action.

“There is a wealth of information available to regulators, and to the public — and most importantly to you. Take advantage of it,” Kider said.

Jourdain-Earl agreed. “We are going to experience a major paradigm shift, and HMDA can be either friend or foe. The responsible thing for lenders to do, is understand what their data is saying,” he said.