If fair housing bluster were an Olympic event, the podium would be crowded with politicians and corporate mouthpieces. The injustice that once provoked marches and protests now evokes photo-ops and press releases.

Barack Obama is president of the United States. Julian Castro is secretary of HUD. Mel Watt is director of the FHFA. Fair housing advocates would be hard pressed to imagine a more powerful, congenial triumvirate. As each assumed his position, the cheers from the fair housing crowd grew louder and louder. Surely the stars are aligned for real progress in fair housing.

Government agencies, along with private organizations and advocacy groups, are in an unprecedented position to promulgate fair housing and initiate/implement programs designed to fight inequity while improving access and choice in housing. So what is happening on the fair housing front? Has President Obama kept his promise from October 2008 when he said we were on the cusp of “fundamentally transforming America?”

You might argue the answer is yes, if by “fundamentally transforming America” you mean talking a lot about fair housing. Talking, tweeting and taking fair housing “selfies.” At the recent Bipartisan Policy Center’s Housing Summit, Castro proclaimed that housing is “back at the top of the national agenda” and that “HUD is the Department of Opportunity.”

But you’d probably have to say no if you meant actually doing much for fair housing. Elizabeth Julian, a former senior HUD official, has said, “The lack of political courage around these issues is stunning… The failures of fair housing are not just by HUD but by the country.”

Perhaps Obama has an excuse. The recent failures of fair housing may be because the president has been mired in the housing crisis, and that crisis has soaked up all his attention and political will. The housing market collapse, which he did not cause but with which he has had to contend, is the 800-pound gorilla, and fair housing has become the lap dog.

To fend off the 800-pound gorilla, the Obama Administration and his allies on the Hill have pushed for and achieved significant housing finance reform. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and Director Richard Cordray have announced they are committed to “ferreting out discrimination in credit markets, including the markets for home mortgages…” and rectifying discriminatory practices through, among other things, supervision, enforcement and consumer education.

At the same time, the CFPB has introduced new Qualified Mortgage standards, which are designed to reduce the risk of mortgage default and should help protect lenders from potential accusations of “predatory lending practices.”

Superficially, opposing discrimination and raising mortgage standards may seem like congruent actions, but the truth is that raising standards comes at a price. Historical and current evidence suggests our methods of evaluating creditworthiness and assessing default risk disadvantage black and Hispanic borrowers.

According to Rob Couch, one of the commissioners for the BPC’s Housing Commission, “there are a lot of crosscurrents here that are difficult to reconcile.” In a recent interview with Housing Wire, Couch suggested that raising the standards so high has resulted in hurting the “very people we are supposed to be trying to help and protect.”

Many fair housing advocates argue that the 43% debt-to-income ratio will make it harder for black and Hispanic borrowers to qualify, but Nikitra Bailey of the Center for Responsible Lending believes the new QM guidelines strike the right balance between the needs of lenders and borrowers. Bailey says that although many have argued QM will decrease access to credit for people of color, her conversations with lenders indicate that the effect on access is negligible.

Terry Francisco, senior vice president with Bank of America, also denies there is an issue, asserting that “for traditionally underserved communities that might have lower down payment funds or credit histories that are not perfect, there are QM loans – including FHA and conventional programs – that are available to qualified low- to moderate-income borrowers.”

Perhaps there are QM loans for the traditionally underserved, but surely not as many. When CFPB advisor Ellen Seidman was a bank regulator during the Clinton presidency, she encouraged subprime lending in “underserved” communities as a means of compliance with the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). “Growth in the subprime credit market indicates that credit needs in many low- and moderate-income areas are being met.”

At the recent BPC Housing Summit, Castro had this to say:

“A few years ago, bad loans and risky secondary market products prompted a housing crisis. There was plenty of blame to go around. Some believe it was too easy to get a home loan. Today it’s too hard.

“The pendulum has swung too far in the other direction. According to the Urban Institute, the average credit score for loans sold to GSEs this year is roughly 750. Currently, there are 13 million people with credit scores ranging from 580 to 680. Many of them are ready to own, but are being left out in the cold. The truth is that the dream of homeownership is out of reach for too many Americans. This has to change.”

Maybe the new mortgage standards are fine according to Bailey and Francisco, but they don’t seem to be fine according to Castro and HUD.

Castro’s HUD and its Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity have other initiatives for Fair Housing. One that recently created an uproar was the proposed update to Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing, where neighborhood diversity data would be gathered to influence communities to change their zoning laws, housing finance policy, infrastructure planning and transportation to alleviate alleged discrimination and segregation. Arizona Rep. Paul Gosar called it an “assault on the suburbs” and the House of Representatives approved an amendment prohibiting HUD from implementing its proposed rule.

Was Castro’s response to this setback to take to the bully pulpit, exert his political will, get the president in on the fight? Not exactly. Instead, he announced his vision for the last years of the Obama Administration.

Was Castro’s response to this setback to take to the bully pulpit, exert his political will, get the president in on the fight? Not exactly. Instead, he announced his vision for the last years of the Obama Administration.

“Across the country, HUD is providing help and hope. And we’ll spend the next two-and-a-half years expanding opportunity for all Americans.”

Sounds spectacular, right? So how is he going to do that? Specifically, he envisions 1) promoting homeownership and 2) improving operations at HUD. It is unclear how improving internal operations at HUD will expand opportunity for all Americans.

Watt was expected and exhorted by some fair housing advocates to usher in a new era in assisting troubled home owners, many of whom were black and Hispanic, with a rush of loan modifications and principal reductions. Instead, Watt has been reserved, more enigma than demagogue.

In a recent interview with Housing Wire, Watt indicated, “the number-one priority for the GSEs is maintaining the credit availability to buy a home.” Not exactly earth shattering, but perhaps calming to a sometimes-jittery mortgage market.

One recent change at Fannie Mae might open up the credit box, at least a little bit. They updated their policy regarding minimum waiting periods for those who had previously gone through a pre-foreclosure sale or deedin- lieu of foreclosure. This change will allow previously distressed borrowers and potential homeowners to seek home ownership sooner. This is a potential boon for home-seekers of all races, but may be especially helpful for those borrowers of color who were more likely to have been distressed.

On the other hand, making it a little quicker for potential borrowers to qualify for a mortgage might not make much of a difference for people who have recently been traumatized by their mortgage going bad in the first place.

At the same time the government is making it harder to qualify for a mortgage, the FHFA has announced they are going to renew the affordable housing goals for the GSEs.

As Couch opined, “You have what appears to be a head-on collision… the banks and mortgage companies don’t want to be anywhere close to marginal loans and, at the same time, Fannie and Freddie are going to have a gun to their head to make more loans to low and moderate income and minority borrowers who, as a whole, have lower credit scores.”

Maybe the government has finally found a way to have its cake and eat it, too — by demanding that other people do it.

IS THERE REALLY A PROBLEM?

In response to the pain of the Great Recession and the collapse in housing markets, homeownership has been dropping, and the once narrowing gap between white and minority home ownership rates is widening again.

Home ownership for whites has fallen to 72.6% , but among Hispanics home ownership has fallen to 45.6% (down 5.97% from its high) and for blacks it has fallen to 42.9% (down 7.1% from its high). The bottom line — blacks and Hispanics are almost 30% less likely than whites to own a home.

Part of this disparity is attributable to the disproportionate foreclosures affecting black and Latino homeowners, and part of this disparity is the result of an overall decline in lending to communities of color.

The Center for Responsible Lending reports that, among recent borrowers, nearly 8% of African-American and Latino homeowners faced foreclosure, compared to 4.5% of non-Hispanic white homeowners.

Jim Carr of The Opportunity Agenda points out that mortgage lending to African-Americans and Hispanics has dropped more than 70% since the housing market collapse.

Even for those blacks and Hispanics that do purchase homes, it’s not all good news. The National Bureau of Economic Research published research which indicates that, for homes of comparable quality and within the same neighborhoods in four major metropolitan areas, blacks and Hispanics pay an average of 3.5% more than whites. For a $200,000 home, everything else being equal, that’s a $7,000 penalty for being black or Hispanic.

Not only are there disparities in homeownership, there are disparities in lending. In early 2014, Zillow and the National Urban League published a report which indicated alarming differences in race throughout the mortgage process.

Whites make up 63% of the U.S. population, are responsible for 69.8% of all conventional mortgage applications, and secure 73.4% of all successful mortgage applications. Hispanics make up 17.3% of the U.S. population, are responsible for only 5.4% of all conventional mortgage applications, and constitute 4.5% of all successful mortgage applications.

Faring worst among minorities, blacks make up 12.1% of the U.S. population, make only 2.9% of all conventional mortgage applications, and comprise only 2% of all successful mortgage applications.

According to the Urban Institute, in 2012 GSE home mortgage denials for black applicants with low credit profiles were 50% higher when compared with white applicants with similarly low credit profiles – 75% and 50% respectively. The data dispels the myth that the only color that matters is the color of money.

Once the mortgage is approved, mortgage servicers manage the day-to-day servicing of the loan. Servicers, responsible for workouts, mitigation, modifications and foreclosures, have been accused of disproportionately disadvantaging borrowers of color. Recently, loan servicers have been implicated in a broad range of activities which some have deemed racist, if not in intent then certainly in impact.

Some servicers have been accused of premature and unauthorized foreclosures and the use of false and deceptive documents (think “robo-signing”). Although all communities were affected by these practices, communities of color were disproportionately affected. If you lived in a predominantly black neighborhood, the chances of your loan servicer approving a loan modification, even if you were eligible, were significantly reduced. At the same time, your chances of being charged unauthorized fees or being lied to about the reason for denying your loan modification went up.

One of the aftereffects of disproportionate foreclosures is the spillover cost, the loss of property value for those who live close to a foreclosed property. According to the Center for Responsible Lending, over half of the $2.2 trillion spillover loss of equity is associated with communities of color. Again, blacks and Hispanics bear a disproportionate share of the burden.

HOW DID WE GET HERE?

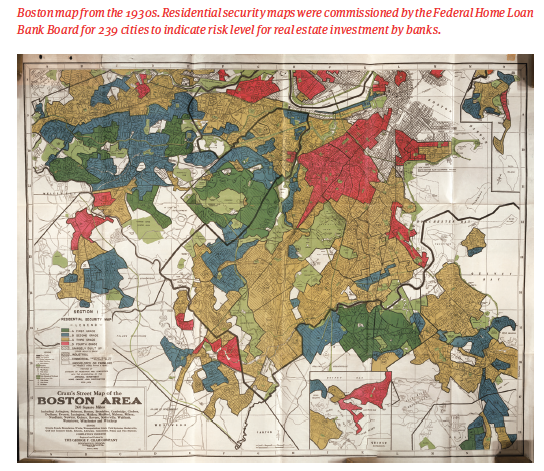

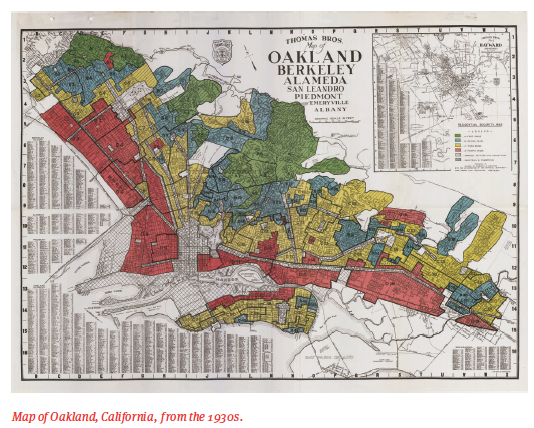

The United States has a long and troubling history of housing discrimination based on race. The de jure segregation of the Jim Crow South was more overt than the de facto segregation of the North, but housing discrimination was epidemic everywhere.

When Americans think about institutional racism, they might think about the pre-Civil War South or the post Reconstruction Jim Crow laws from the late 1800s. Unfortunately, governmentally sanctioned racial discrimination was much more pervasive, pernicious, and enduring (see sidebar on the next page).

Since 1968, various laws have been enacted to bolster the legal force and effect of fair housing laws. With data disclosed in compliance with the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (1975) and the mandate for lending institutions to reinvest in the communities they serve in accordance with the Community Reinvestment Act (1977), fair housing advocates began pressuring lenders to make mortgages available to previously underserved populations.

With deregulation, banks and other financial institutions began competing for customers with a wider range of products and services. The Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 abolished state caps on mortgage interest rates and made it possible for lenders to charge higher interest rates to riskier customers.

The Alternative Mortgage Transactions Parity Act of 1982 made it possible for lenders to make nontraditional mortgages with adjustable rates, balloon payments, interest-only options, etc. According to Bailey at the CRL, minorities were frequently and disproportionately targeted for these higher interest rate, riskier nontraditional loans.

At the same time, the U.S. government made it clear that deregulation was more than just an opportunity to gain new customers, but a chance to bolster fair housing efforts. Court decisions such as Havens Realty v. Coleman (1982), laws such as the Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988, and the leadership of Henry Cisneros as HUD Secretary all suggested that fair housing was paramount and the government would act accordingly.

Armed with greater flexibility and the government’s blessing/mandate, lenders went on a lending spree. Home ownership rates rose to an all time high for everyone, including Hispanics, African-Americans, minorities, city dwellers and households with less than median income, and it seemed like the home ownership party would continue unabated. U.S. home ownership hit an all time high of 69.2% in the fourth quarter of 2004.

Shortly thereafter, with the onset of the Great Recession, the housing bender turned into a housing hangover, and the hardest hit were those with nontraditional and higher interest rate loans. The collapse affected homeowners across America, but the effects were particularly devastating for communities of color.

The average American family’s household net worth declined 20% between 2007 and 2009, and the value of primary real estate holdings decreased by an average of $18,700. The median net worth of Hispanic households fell by 52% and that of black households by 30%.

NEXT STEPS

If real change is to take place, it will likely be the result of some combination of public and private action, relying on programs that have proven useful in the past while innovating new ways to improve the plight of traditionally underserved people, including communities of color.

But among people in a position to do something, there must be more than just talk about making a difference—there must be the will to act.

Couch suggests that to move housing forward, we need to reframe the discussion and ask, “What is the overall goal?” Couch suggests that instead of debating “how we can punish” entities that made questionable loans in the past, we should be asking what an acceptable level of non-performing loans might be.

According to Couch, our recent pattern of “trying to structure a system where no loan is ever going bad” is unrealistic and stifles homeownership. Because of the antipathy toward past bad actors, Couch believes “there is a tendency for vendors to say we don’t want to have anything to do with less-than-pristine mortgages, because anytime a loan goes bad it’s our fault.”

Couch says, “Homeownership is a good thing for the country and we ought to be encouraging people who have a reasonable chance of repaying their loans, giving them a chance. We need to define what reasonable is, and that’s a debate that just doesn’t seem to be taking place.”

Ed Pinto, resident fellow and codirector of American Enterprise Institute’s (AEI) International Center on Housing Risk, asserts that “a housing policy that has relied on ever looser underwriting standards in an attempt to lift the homeownership rate for low- and moderate-income homebuyers, many of whom are minorities… has failed miserably.” Instead of making home loans riskier, Pinto argues that a better solution is modeled after the FHA’s response to the real estate collapse of 1927, which they called “a straight, broad highway to debt-free ownership.”

The AEI, in collaboration with the Neighborhood Assistance Corp. of America and Bank of America, has recently announced what they are calling a Wealth Building Home Loan, a program which they believe will reduce the risk of foreclosure by improving common-sense underwriting and amortizing much quicker than a traditional 30- year loan. Targeting a broad range of homebuyers, including low-income, minority, and first-time buyers, the loan “requires little or no down payment and has a broad credit box, meaning sustainable lending for a wide range of prospective homebuyers.”

Congresswoman Maxine Waters is taking a different approach, seeking to change the way people evaluate and determine creditworthiness. She recently introduced the Fair Credit Reporting Improvement Act of 2014, which would make several changes to current credit scoring practices, including removing negative information from a credit report after four years instead of seven, removing all debt settlements from the report and eliminating medical debt from credit reporting.

The CFPB has published research that “credit scoring models may underestimate the creditworthiness of consumers with medical debt collections,” and medical debt has been a huge encumbrance on the credit score and home buying potential for many Americans. If Waters has her way, credit scoring will change and an army of potential homebuyers will be closer to realizing the American Dream.

LEAVING A LEGACY

There has never been a more advantageous time in America to make substantial progress in fair housing, and the next two years will be pivotal. As we recover from the Great Recession and the collapse of the housing market, change is everywhere. Decisions being made during this time of disruption may very well solidify into the policies of the next generation.

Will politicians, corporations and advocacy groups take advantage of this opportunity to make a substantial difference in the lives of traditionally underserved communities of color, or will we continue with the status quo? Obama’s time is running short, and he may be looking for a legacy. Will he find it in fair housing?

Speaking at the LBJ Library’s Civil Rights Summit, Obama described President Johnson’s leadership in the Civil Rights Movement.

“That’s where he meets his moment. And possessed with an iron will, possessed with those skills that he had honed so many years in Congress, pushed and supported by a movement of those willing to sacrifice everything for their own liberation, President Johnson fought for and argued and horse traded and bullied and persuaded until ultimately he signed the Civil Rights Act into law.

“And he didn’t stop there — even though his advisors again told him to wait, again told him let the dust settle, let the country absorb this momentous decision. He shook them off…Immigration reform came shortly after. And then, a Fair Housing Act.”

As Obama has reminded Congress, “I’ve got a pen . . . and I can use that pen to sign executive orders and take executive actions.”

The question is, will he use it for fair housing?