Lumping millennials, 18-34 year olds, together into one demographic may not sit well with those who argue the group is too diverse to target.

But one analyst at Goldman Sachs (GS) is asking when will these “kids” ever move out of their parents' basements.

Analyst Hui Shan is asking the question because this is a huge potential demographic of first-time homebuyers.

After crunching some numbers, Shan concludes that ultimately millennials will need to get jobs to get them to finally move out. This process, parents will be sad to learn, may take many, many more years.

"As long as economic recovery and labor market improvements continue, household formation should eventually normalize," Shan writes. "Given the severe damage caused by housing busts to the economy, the process of normalization may take a number of years."

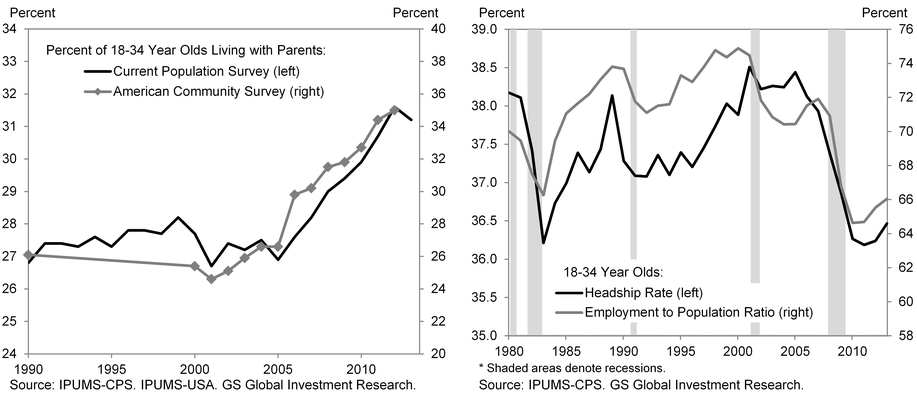

Shan notes that there is a massive pent-up housing demand compared to pre-bust years. In the early 2000s, for example, around 25% of young adults lived with parents. Today, that number hovers closer to 35%. This chart shows the landscape:

“As the labor market continues to improve, we expect to see young individuals move out of their parents' basements and live independently, boosting both household formation and construction activity,” Shan said today in a note to clients. “Today, we look beyond the national series and bring together two pieces of regional evidence to support this constructive view.”

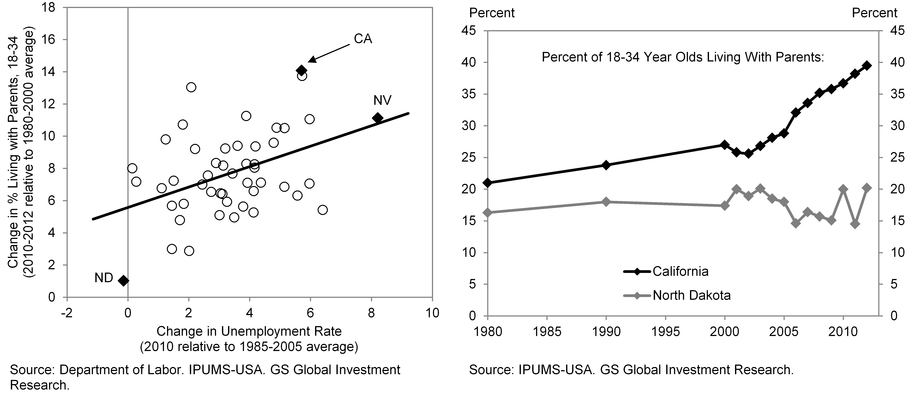

That regional evidence is a snapshot of millennial behavior in California versus North Dakota:

"We compare California, where the unemployment rate shot up from below 5% in 2006 to over 12% in 2010, with North Dakota, where the unemployment rate peaked at 4.2% in 2009 and remained below 3% over the past year. While the share of young individuals living with their parents increased from 26% in the early 2000s to 40% in 2012 in California, the share of 18-34 year olds living with parents stayed little changed in North Dakota."

"This evidence suggests that the depressed level of household formation among the young in recent years is a product of the weak labor market rather than structural shifts in preferences."

All is not lost, however. Shan notes that when comparing similar market conditions in California in the 1990s, New England in 1988 and oil-rich states in the early 80s, those markets eventually relieved themselves of kids over-inhabitating their spaces.

"The average household size increased during the first few years of each housing bust, presumably driven by young individuals living with their parents and roommates doubling up to save rent. Over time, the effect reversed itself and average household size retraced the earlier increases, translating into increases in household formation. Because of small sample sizes, the estimates are not precise. But the pattern of first increasing, and then decreasing, household size is visible in the three episodes that we study."